Charlton McIlwain | September 16, 2020

Why is this interesting? - The Race & Barbecue Edition

On cooking, COVID, and anti-Black violence

Recommended Products

![Pitmaster: Recipes, Techniques, and Barbecue Wisdom [A Cookbook]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.interesting.us%2Fproducts%2Fpitmaster-recipes-techniques-and-barbecue-wisdom-a-cookbook-fdfad7b1-7a15-4926-89bb-a3600c67de77.png&w=640&q=75)

A book that provides insight into the art of barbecue, part of a long tradition of such guides.

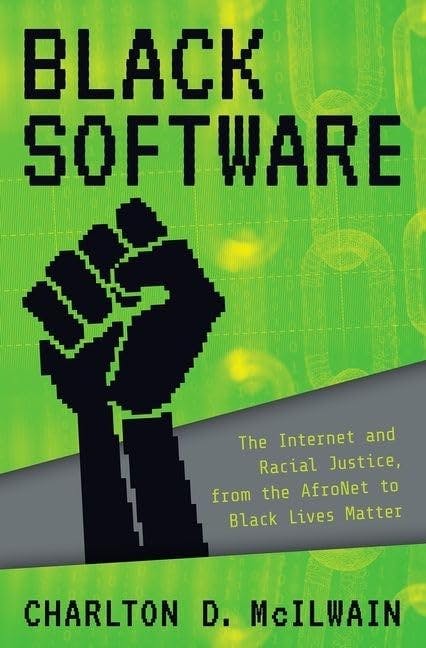

Charlton McIlwain (CMD) is a Vice Provost and Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at NYU. He’s also the author of Black Software: The Internet & Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter, which is out now on Kindle and will be available in hardcover come November. I was introduced to Charlton when I was 19 and he became my advisor at NYU. He was an amazing mentor through four years of exploring the past and present of media, culture, and technology, and helped kindle my appreciation for many of the topics I obsess over in these very emails. Thanks, Charlton. - Noah (NRB)

Charlton here. Since COVID-19 quarantine first began, I took refuge in my small backyard space in downtown Brooklyn. At first, just being outside made life a bit more bearable. It was a space where I could feel the sun on my face as I rotated from Zoom to Zoom. It was a space where I could hear chirping birds, barking dogs, and the hum of neighbors’ yard work—a much-needed break from an eleven-year old’s Fortnite noise.

But by the end of May, my space had transformed into something more. George Floyd and Breonna Taylor had been tragically murdered; at the time, they were the latest of the all-too-common Black deaths caused, or not deterred by law enforcement. People took to the streets to protest. To get Justice. To let the world know that Black Lives Matter. As the protests intensified, my backyard became the place where I experienced those daily uprisings. I followed the protest cadence through the rattle and hum of helicopters lighting atop my block, crisscrossing to and through my neighborhood.

But at the same time that my space had become the medium by which I connected to the violence and pain wrought by two pandemics, I did so, gazing at my family of six grills (recently downsized from seven). The largest is an Oklahoma Joe smoker that can fit enough meat to feed a hundred; the smallest, my mini-Weber, perfect for a small portable feast with family and friends. So just as much as being outside reminded me of the continuous spectre of systemic racism, anti-Blackness, and police brutality, I could not help dwelling on the art, the hobby, the pastime we call, barbecue.

Why Is This Interesting?

Those early summer moments reminded me once again how much race and barbecue have been so twisted and tied together in this country, from our present day, back to Jim Crow, emancipation, and all the way back to slavery. On June 4, David McAtee, a Kentucky gentleman affectionately known as “Barbecue Man,” was shot and killed as the National Guard was ordered into Louisville to “keep the peace” amidst Black Lives Matter protests. Mother Jones writer Jamilah King observed that “The seemingly small actions at barbecues and of bird watching had to inevitably lead to something larger.” And, as summer approached, U.S. news outlets inked no shortage of public interest stories instructing people how to safely enjoy some good ‘ol ‘cue in the midst of the neverending pandemic.

Race. Violence. Freedom. Struggle. Entertainment. Politics. These are, and have always been, the seemingly contradictory threads running through America’s regional barbecue tapestry. For example, take this Reconstruction-era scene that I wrote about a couple of years ago when I was working on a still yet-to-be-finished book on race and barbecue:

“Smoke!” That's what the correspondent from the New York Herald observed when he arrived in Atlanta, Georgia in the summer of 1868. But Georgia wasn’t burning; it was cooking! “Free barbecues,” he exclaimed, “are being held at the rate of five or six every week.” Drippings from well-marbled meat – sixteen hundred-pound oxen, passels of hogs suspended over a deep pit – wafted a familiar aroma through the wide-open fields that just months before were strewn with Rebel bodies and soaked with Southern blood.

But seeing those gathered to consume the mass delectables really took this Yankee stringer by surprise. White people. Black people. Former masters mixed and mingled with their former chattel. Just three years prior, slaves might be strung up for the mere thought of openly addressing a white man (much less a woman). But that sultry summer, newly-minted Negro leaders’ soaring oratory dazzled crowds of their former masters and misses. They listened as their colored friends summoned tempered passions and the strength of reason many thought not possible. As that nameless reporter told it, the scene was nothing short of idyllic. And it was this “entente cordiale, this good feeling, this disposition to support each other now exhibited by the two races” that so compelled him to tell his story on the pages of his home state Herald, as well as in a letter penned for Atlanta Journal Constitution subscribers on August 20, 1868.

Of course, those particular good feelings didn’t last. Reconstruction turned too quickly to widespread anti-Black violence, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow-era segregation. Black and white folks parted ways, and so did their barbecue. But the point of that Yankee stringer’s story was about the potential for barbecue to produce that good feeling, to bring people together.

My point? A summer of racial violence, pain, and protest leads someone like me to feel like I am standing in Sociologist W.E.B. DuBois’ shoes, late in the summer of 1897. That’s when he famously wrote these words in the pages of The Atlantic:

Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

Now, I suspect that DuBois “answered seldom a word” because he knew that doing so would create an inescapable burden. A burden to express one’s personal feeling. A burden to explain one’s experiences. A burden to act. A burden that would define one’s life and work and worth and crush you in the process.

My point? Throughout this summer I have—like so many friends and colleagues like me— taken up this burden. We are compelled. It is our work. We take it up willingly, but not without consequence. Alicia Garza tweeted early this summer that “...Black people are exhausted. I’m exhausted. Angry. Devastated. Scared.”

It is in this context that I think about that “good feeling” induced by barbecue. Communing with wood and fire. Trimming fat from a well-marbled brisket. Minding my smoker’s temperature to steadily run low and slow. Pulling off a heavy-barked, juicy handful of a twelve- hour-smoked pork shoulder. Pure joy

In the midst of it all, that is the point. (CDM)

Book of the Day:

Pitmaster is a recent addition to a long line of books that provide great insight into the pure, unmitigated joy in the art of barbecue. (CDM)

Quick Links:

As a near Native Texan, I’ve long been a fan of Texas Monthly magazine. In addition to featuring some of the best investigative reporting and informative state travelogues, they are all about the Texas ‘Cue. Over the years, their features on the history of race and barbecue and its role in the creation of race and Texas barbecue have made for some good learning.

How African American Visitors Found Texas BBQ During the Jim Crow Era (CDM)

Juneteenth and Barbecue (CDM)

I’ve also been enjoying this new series on Netflix that connects the stories of present-day pitmasters to the racially diverse barbecue traditions that have evolved through history.

Chef's Table: BBQ (CDM)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Charlton (CDM)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).