Colin Nagy | August 5, 2020

Why is this interesting? - The Ventilation Edition

On offices, air, and the challenges of keeping buildings well-ventilated

Recommended Products

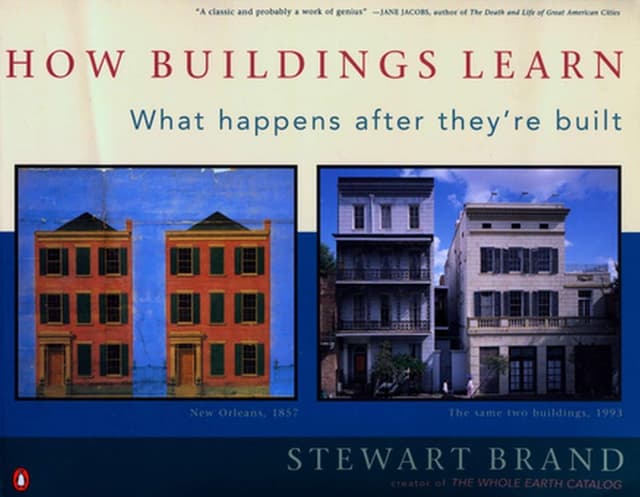

Brand proposes that "...buildings adapt best when constantly refined and reshaped by their occupants, and that architects can mature from being artists of space to becoming artists of time...More than any other human artifacts, buildings improve with time—if they’re allowed to." The book shows how to work with time rather than against it.

Abe Burmeister (AWB) is the founder of Outlier, a favorite of WITI. They make beautiful clothing out of interesting, technical fabrics that are quietly bombproof. Abe has been a longstanding writer and thinker, back to the early days of the blogosphere, through a cult site called Abstract Dynamics, which hosted incredible writers like the late Mark “K Punk” Fisher, Philip Sherburne, and Sasha Frere Jones. He’s one of the most interesting and opinionated people we know, and we are very happy to have him on the page today. -Colin (CJN)

This is the time of ventilation, the forgotten V in your HVAC system (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning). There is growing consensus that COVID-19 spreads most virulently via prolonged airborne exposure indoors. Outdoor transmission definitely happens, but is relatively rare—contract tracing of super spreader events almost always points towards indoor spaces where individuals linger around. Ventilation is the term for bringing outdoor air indoors, and most Americans spend 90% of their lives inside buildings. Ventilation can bring the safety of outdoor air indoors, or be the mechanism that shuts it off. As we try to reopen schools and offices, ventilation is life and death, and it is almost entirely invisible.

Why is this interesting?

One of the dirty secrets of modern architecture and real estate is that most buildings are very poorly ventilated. There is no building standard for good ventilation, only a standard for minimum viable ventilation. Most buildings get built to meet only this minimum, and they only need to meet even that threshold at the time of construction. Once a building is approved to open, the maintenance of ventilation levels is entirely in the hands of the management. And good ventilation, at least in how it's handled in modern buildings, is expensive to keep up. An office, classroom, or apartment built in the past fifty years is almost certainly bringing in far less fresh air than is optimal, even before the current pandemic. Outdoor air pollution gets all the attention, but indoor air quality levels are often significantly worse than outdoors, filled with volatile organic compounds (VOCs), formaldehyde, and CO2 from human breath, on top of all the small particulate matter also found outside. Bad ventilation was already a blunt threat to your health, but now it's also apparently a prime vector for coronavirus transmission adding a sharp edge to a hidden problem.

Auspiciously published in late April this year is a book called Healthy Buildings: How Indoor Spaces Drive Performance and Productivity by Joseph Allen. It's both extremely timely and also one published way too late. Ventilation is just one part of what makes a healthy building, but Allen ranks it as by far as both the most important and easiest to fix of the nine criteria he uses. And fixing it just might be crucial in rebooting our virus-ravaged world. While exact data is hard to come by there is good reason to believe a well-ventilated room is dramatically safer than a poorly ventilated one. Asian authorities have been warning their population to avoid poorly ventilated spaces since early in the pandemic, most notably in Japan's "Three Cs", which has C #1 to avoid as "Closed Spaces with poor ventilation".

It's easy to say "avoid spaces with poor ventilation", but in practice, it's hardly obvious what spaces are well-ventilated and which are not. There are clues to look out for, though. The most obvious is open doors and windows: the more open a space is to the outdoors the better, especially if there are openings on multiple sides to provide cross-ventilation. Beyond that things get a lot more subtle. Often we can feel when a place has no airflow—that stuffy warm sleepy feeling of a conference room or airplane during boarding. (Once airplanes leave the gate and turn on their systems they actually have excellent ventilation though.) Sometimes one can actually feel the airflow or notice tiny flags attached to vents moving, but airflow is not the same as ventilation. HVAC systems generally combine outdoor air with recirculated indoor air for reasons of energy efficiency. The indoor air has already been cooled or heated to the target temperature, while fresh outdoor air generally needs far more cooling or heating to keep the indoor air synced to the thermostat. The cool breeze coming from an air conditioner might be fresh and filtered, or it might be recirculated breath piled on recirculated breath until a deadly viral load is achieved. And sure enough, some of the most detailed contract tracing studies of superspreading events tend to see transmission patterns that closely trace airflow from air conditioning. The crisp cold feeling of an air conditioner is not fresh air, it's a warning sign.

New York City began reopening right as spring turned to summer, and stores that once were propping their doors wide open for airflow suddenly began shutting them closed to keep in the cold air. In fact, in New York they are legally obligated to do so, a fact that clearly illustrates the fundamental challenge of good ventilation. The law, passed five years ago, came with the purest of intentions: it was there to prevent excess globally warming energy use from stores trying to lure in customers with blasts of cold air from their open doors. Closing the doors, keeps the cold air inside, reducing the amount of air conditioning usage. But it also reduces ventilation, trapping employees and customers together with cold recirculated air.

Ever since the energy crisis in the early 1970s, buildings have been optimized towards energy-saving. If Allen's book suffers one unfortunate flaw it's that he spends far too much time building counterarguments to these economics, only to have the damn virus render them irrelevant. The fact that increasing ventilation can lead to healthier and more productive environments, and thus higher rents, is probably true, and Allen argues this in-depth. But it's also quite irrelevant in a day and age where improving ventilation is no longer a matter of saving a few pennies, it's the difference between life and death. (AWB)

Book of the Day:

How Buildings Learn by Stewart Brand (of Whole Earth Catalog fame) that proposes “...buildings adapt best when constantly refined and reshaped by their occupants, and that architects can mature from being artists of space to becoming artists of time...More than any other human artifacts, buildings improve with time—if they’re allowed to. How Buildings Learn shows how to work with time rather than against it.” (CJN)

Quick Links:

A updating thread on the explosion in Beirut (CJN)

Hackers broke into news sites to plant fake stories (CJN)

Wow: Katie Ledecky swimming the length of a pool without spilling a single drop of the chocolate milk balanced on her head. (CJN)

Encyclopedia of Flowers (AWB)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Abe (AWB)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).