Stephanie Balzer | February 15, 2024

The Artist’s Work Edition

On purpose, compromise, and permission

Steph Balzer (SB) writes Cento and works as a coach. She previously contributed The Organizing Edition, The Emotional Language Edition, and The Art in Vegas Edition, all with ties to Las Vegas, and The McLuhan Edition, which is also about a creative person.

Steph here. Las Vegas is among the largest cities in the United States without a fine arts museum.. I had to let a part of me go when I learned this about my new home. Next to coffee shops and the occasional bar, museums and airports have been two of my favorite places to write, daydream, and sink into curiosities about the people around me.

Airports lost their romance long ago, for reasons I likely do not have to spell out (but also I kept missing flights.) And without the traditional museums, Vegas provided me an opportunity to evolve how I experienced art, which has generated several Vegas-art-themed WITIs, and is also why I recently ventured to the Rita Deanin Abbey Art Museum.

Opened to the public by appointment in 2022, the museum is a 10,500-square-foot sanctuary in the scruff of the city, about 20 miles northwest of the Strip. The late multidisciplinary artist's works are settled here, in a rural neighborhood flaunting a mishmash of architectural styles that include old ranch homes, Mexican-inspired casitas, Winnebegos and trailers, road signs warning of horse crossings, and scrubby desert vistas. This is where Abbey lived with her second husband, a retired pathologist, after moving to Vegas in 1965.

Why is this interesting?

A few times in my life, I’ve had encounters with artists that have granted me permission to be more of who I am. I came to the museum prepared to look at some paintings, maybe get a story. I left having met a woman who stood in the conviction of her life’s work.

A closeup of Jacob’s Ladder, 1987 (From Desert to Bible Vista Series, acrylic on canvas, 1979-1987)

“I am in search of my nature,” Abbey once said, “and the nature of materials, and the world around me.” She had a metaphysical, physical, and demanding art practice. Her work is industrial, architectural, cosmic and organic, and she continuously evolved her aesthetic. It’s almost as if she would sink into a rhythm and then intentionally disrupt it, at times working against beauty or resonance, because that is not the edge from which we learn.

As I wandered through the gallery, the only visitor, Abbey’s husband came to say hello. We stood next to a cast bronze sculpture of an outsized figure practicing tai chi. “She knew 173 poses,” he said of his wife, who passed away in 2021 at age 90. “I can’t remember her instructor’s name—I wish I could remember his name.”

The tai chi figure has a spine of prickles, like the ridgeback of a lizard. A similar sculpture of her son, a dancer, wears a mask of a mountain lion. He looks alien or other, even beyond being giant. Both figures have perfect, symmetrically-formed fingers and toes.

A closeup of Maui,1969 (From the Black Art Series, polyurethane foam, resin, and sand on plywood, 1967-1970)

“How important is work to you?” an interviewer once asked Abbey. “It’s what my life is all about and I try to work everyday,” she replied.

In my circles, we call this “purpose,” when you are living in alignment with a deep sense of self. Yet Abbey’s adhering to work as a sense of purpose did still strike me as bold. I liked that she said her life was about “work” rather than “art.” This was her ridgeback spine: discerning, emotionally pragmatic, unromantic. Engaging with her curiosity, yes, but not trying to soften the reality of what is.

It also eschews the cautionary tale we’ve all heard, that you will regret this on your deathbed, that a life of work is not a life well-lived. I’ve typically considered this an affliction of men—the picture I conjure is of an executive straight from central casting, bereft of intimacy or true relationships, having lost the bet that success could buy him transcendence. I never imagine a woman. Women have hardly been afforded permission to make that same proverbial mistake.

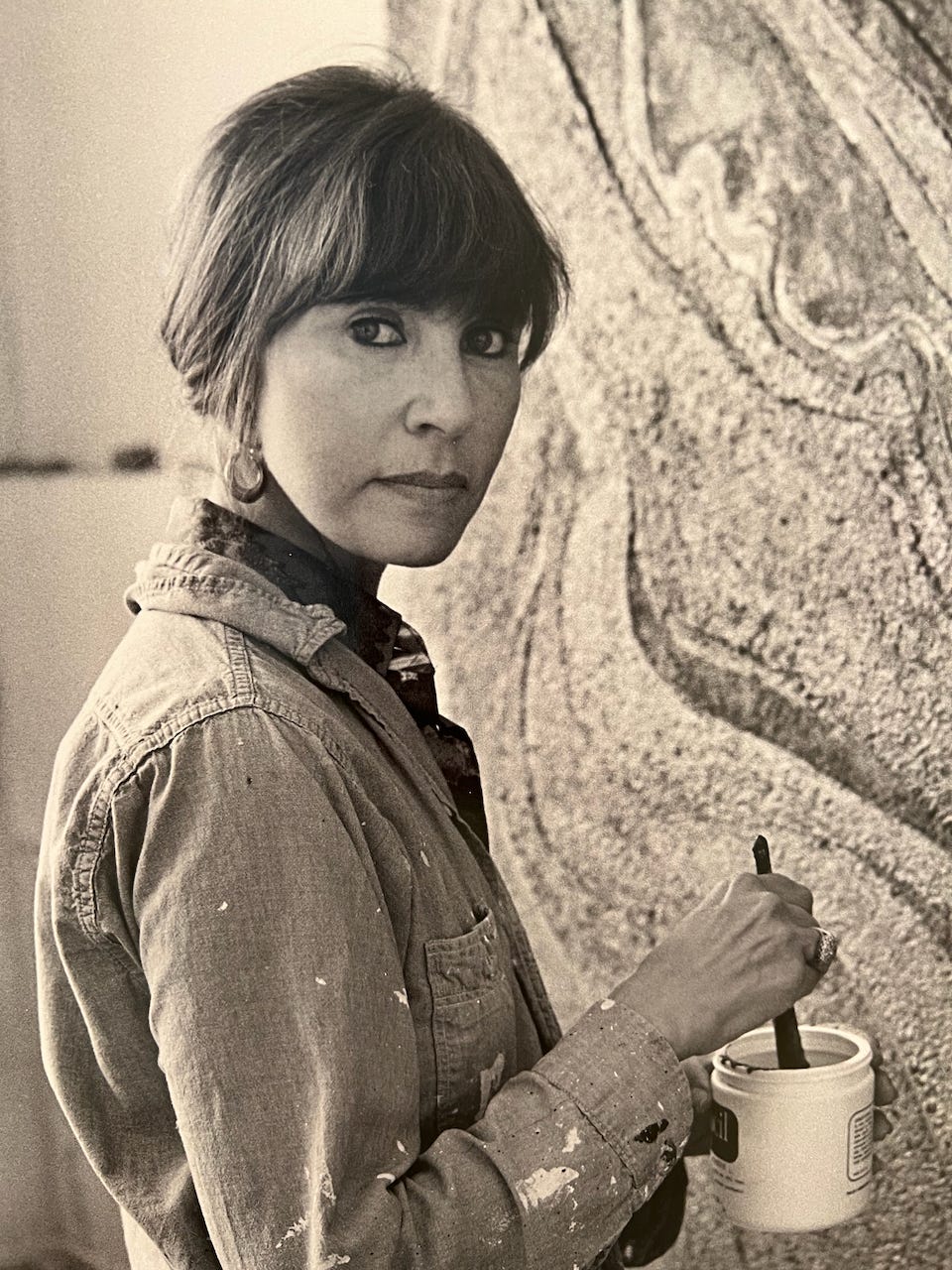

Rita Deanin Abbey

I also wrestled with Abbey participating in the concept and creation of her own museum. (Can you do that? Make a museum for yourself?) Again, Wikipedia has a page for museums dedicated to single-artists, and of the 180-something listed, only a handful are women. “She was tough,” Abbey’s archivist told me, gesturing with her hands like she was pounding on metal. “And she always dressed like this,” she added, pointing to a photograph of Abbey in men’s clothing. “This was probably her son’s shirt.”

As a writer, gender is a newer lens through which I am viewing the world. Perhaps I’m in my Barbie phase, or else it’s simply my time to reconcile with these dynamics. Previously, I likely would have considered Abbey solely from the perspective of the artist regardless of gender, but understanding Abbey as a woman, reminded me to trust myself.. To write what I want. To build what I want. To pour as much of myself into my work as I want. (SB)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Steph (SB)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).