Noah Brier | September 1, 2020

Why is this interesting? - The Federal Architecture Edition

On drafting, building, and beauty

Recommended Products

A series focused on homes that adapt to landscapes, with each episode spotlighting architecture that complements its natural surroundings.

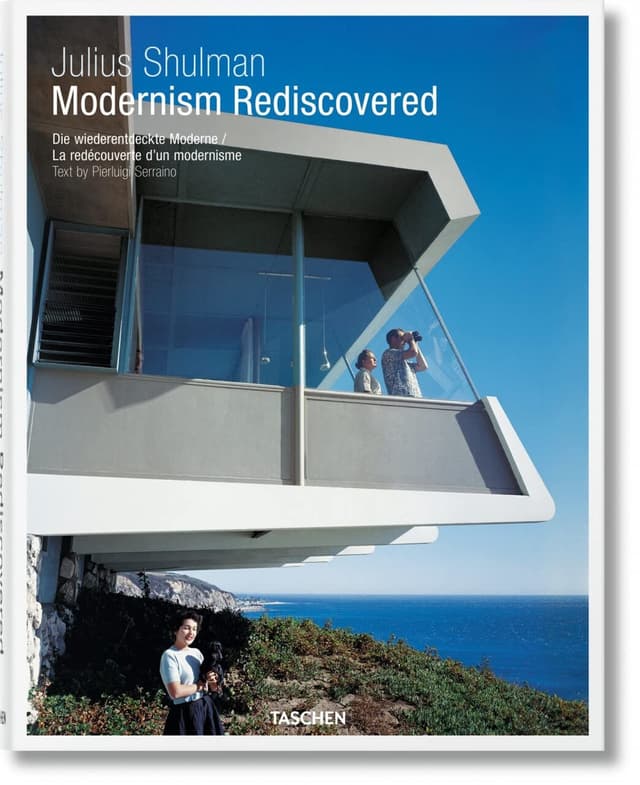

Examines 400 of Julius Shulman's pictures, known for his photographs of Mid-Century Modern architecture in California.

Praveen Fernandes (PF) is my brother-in-law and a previous WITI contributor (the very excellent Owl and Stamps Editions). His bio is far longer than I could list here, but briefly, he’s a lawyer, advocate, former Obama administration appointee, and art lover. - Noah (NRB)

Praveen here. In early February, amidst events like the Superbowl and the Iowa Caucuses, something else happened that captured less attention—various publications, such as Architectural Record and The New York Times, appear to have gained access to the draft of an executive order that, if finalized and issued, would establish that “classical architectural style shall be the preferred and default style” for all new and renovated federal buildings. For those who don’t follow architecture closely, the classical architectural style referenced in the order is a style that harkens back to ancient buildings built by Greeks and Romans from the 5th century BCE to the 3rd century CE. Think the Acropolis and the Pantheon. Envision columns and pediments, in materials like marble and stone. The draft executive order criticizes the General Service Administration, an independent federal agency that manages federal properties and oversees much of the contracting for the federal government, and in particular, its Design Excellence Program.

The Supreme Court Building by Cass Gilbert

Why is this interesting?

While many executive orders end up getting politicized on substantive and procedural grounds—and this draft executive order likely will prove no exception—there is a compelling history behind the existing Guiding Principles that inform the Design Excellence Program’s approach to shaping federal architecture.

The current system establishes parameters and principles for federal buildings, but in terms that are purposely open-textured. Issued in 1962 and derived from a report authored by a young (pre-Senate) Daniel Patrick Moynihan to President John Kennedy, the Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture require: (1) the design of federal buildings to provide “efficient and economical facilities” for government use; and (2) “provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability” of American government. The principles aimed to ensure that good design wasn’t considered an afterthought, and the document continues by saying:

The belief that good design is optional, or in some way separate from the question of the provision of office space itself, does not bear scrutiny, and in fact invites the least efficient use of public money.

The principles specifically state that “the development of an official style must be avoided” and go on to quote Pericles’ instruction to the Athenians, “We do not imitate—for we are a model to others.”

As a drafting matter, Moynihan and his team wisely avoided being overly granular. By establishing goals like buildings that provide visual testimony to “dignity” and “vigor,” but not being overly specific about what dignity and vigor translate into, the principles have remained relevant and powerful without being overly prescriptive or needing to be updated. We see the wisdom of this approach to drafting elsewhere. For instance, examining one of the U.S. Constitution’s strongest and most vital provisions, the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection language (preventing the denial of “any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”), it establishes a clear commitment to equality without being overly granular. This has permitted fidelity to the text’s equality mandate, while protecting the rights of a number of groups of people (such as the LGBTQ community of which I’m a member) whose struggles might not have been specifically contemplated by the Framers. We can benefit from broadly stated principles, which can be applied in successive generations based on the reality and demands of the moment.

There is also a humility to this approach. It’s hubris to think we know what will evoke dignity in the years ahead. When I was 11, I was fairly sure that my sleeveless vest and parachute pants constituted enduring elegance. (I was wrong, Gentle Reader. So wrong.) To cite an architectural example, consider Brutalism. This style (with its simplicity, rough edges, and abundant use of concrete) might have fallen out of favor for some time, but it is experiencing a comeback. And buildings like the Barbican in London and City Hall in Boston are finding legions of new fans, like the architectural equivalent of high-waisted pants.

J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building by Charles F. Murphy and Associates

The Guiding Principles avoid isolating any strands of America’s architectural DNA and amplifying them over others. This allows for the sort of regional variations in the built environment that one sees when taking a road trip across the country. To name just a few examples, one can observe Spanish influences in Florida, Mexican influences in Texas, and Japanese influences in California. And of course, the architecture of a region doesn’t just reflect its people and cultural history, but also the practical realities of building in that region. A flat modernist roof might work well in Palm Springs, CA, but might be a disaster in a state with heavy snowfall, like Vermont.

U.S. Courthouse for the Utah District by Thomas Phifer and Partners

Finally, the flexibility of the Guiding Principles has permitted federal architecture to adapt to new challenges. Knowledge about the climate change crisis and the environmental impact of building has changed how architects approach their work. Why shouldn’t buildings in the Pacific Northwest be able to use locally sourced and reclaimed timber? Why shouldn’t buildings have flat, green roofs? Foreclosing these simply because they don’t mesh with a particular style would be foolish. Also, what about other challenges? Security screening measures implemented after September 11, 2001, have meant that the grand central entrances of such classical buildings like the Supreme Court have been closed to the public, in favor of side entrances that facilitate screening. What adjustments will the COVID19 crisis bring us? A recent WITI discussed the importance of considering HVAC in buildings, but might we also discover that the large central halls and formal entrances of classical buildings make less sense than buildings with multiple entrances (to avoid large groups of congregating people) and ones that make use of indoor and outdoor spaces? As the nation navigates this current deadly pandemic—and constructs buildings to lessen the impact of future pandemics—the Guiding Principles don’t limit architectural problem-solvers to the constraints of a particular style.

The Guiding Principles aim for beauty in our federal buildings, but avoid the trap of narrowly defining what is and could be beautiful. (PF)

House of the Day:

Utsav House is in Alibagh, India, just on the outskirts of Mumbai. This New York Times article is a thoughtful exploration (with striking pictures) both of architectural influences in India and the experiences (including family tragedy) that shaped the approach of the architect, Bijoy Jain. (PF)

Quick Links:

What’s in a name? The proposal for rebranding Brutalism as “Heroic” architecture. (PF)

“The World’s Most Extraordinary Homes” is a Netflix series that I feared would devolve into a sizzle reel for mansions, but it ended up being something much more interesting. Season 1 focused on homes that adapted to landscapes, with each episode (Mountain, Forest, Coast, Underground) spotlighting architecture that blended and complemented its natural surroundings. (PF)

Julius Shulman was a photographer most known for his pictures of Mid-Century Modern architecture in California. His photo of Case Study House #22 is iconic. Modernism Rediscovered examines 400 of his pictures. (PF)

Ruth Asawa, an artist whose sculptural (and quasi-architectural) works were underappreciated during her lifetime, is gaining a USPS stamp and new fans. (PF)

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Praveen (PF)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).