Colin Nagy | January 18, 2023

The Walking Tokyo Edition

On phases, Japan, and sprawl

Recommended Products

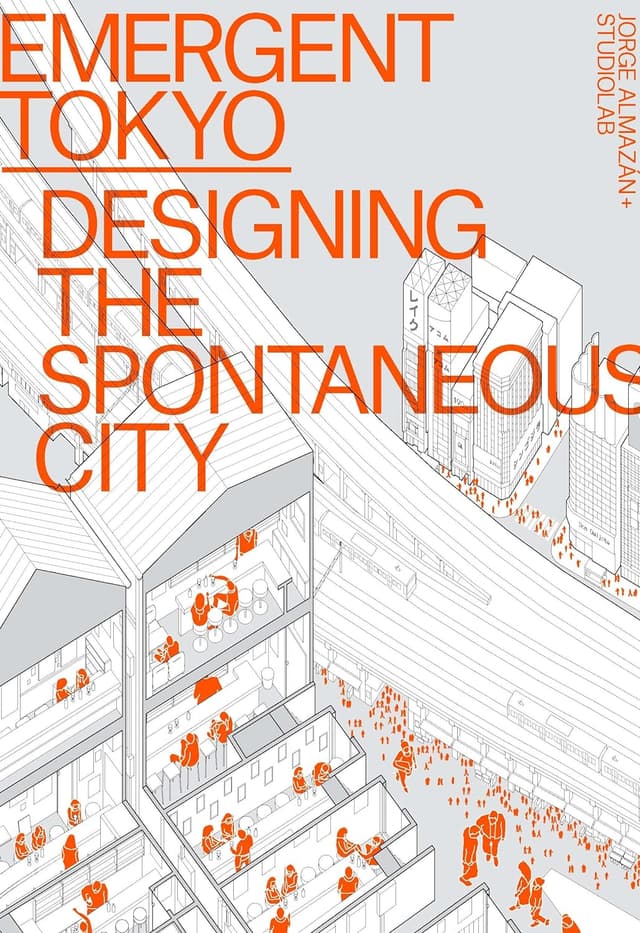

The book outlines the organization of neighborhood shop-owner collectives in Tokyo to protect the energy and community of sometimes centuries-old neighborhoods amidst the city's rapid development.

Craig Mod is a walking writer and photographer. We had the pleasure of catching up when I was in Tokyo in December. You should peruse his newsletters, including the interesting pop-ups, and also his shop. -Colin (CJN)

Once again I’m walking Tokyo. I mean, I’ve been walking Tokyo for twenty-two-and-a-half years, but I’m “performing” another dense, seven-day mega walk of the city starting on Tuesday. The goal with these walks is to look closely at the city, mostly offline, with minimal distractions, and maximal control of attention and openness of mind.

The best way to know a city is to walk a city. And the best way to *really* know a city—a thing that has no static configuration, that is forever morphing, changing based on politics and laws and immigration and culture and industries and natural disasters and aging populations and other unseen global forces—is to *rewalk* and to do so over decades.

I find that subways divide a city in the mind, that each station becomes an island. The notion of getting from one station to another without hopping on a train becomes unthinkable. It took me years to realize you could walk from Asakusa to Shibuya in a couple hours — those two places felt as far away as Istanbul from Paris. But, no, not only can you traverse the distance on foot, but the incredible diversity and density of a city like Tokyo rewards the walker each and every block.

WITI Classifieds:

We are experimenting with running some weekly classifieds in WITI. If you’re interested in running an ad, you can purchase one through this form. If you buy this week, we’ll throw an extra week in for free on any ad. If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to drop a line.

Supercharge your lifelong learning. Upnext lets you save any content, and actually get to it later. Supports articles, podcasts and video! Try Upnext for free

For 10 years, this has been the go-to newsletter for people who like to keep up with what’s exciting in design, books, beauty, food, & more. Subscribe

For the inner journey. For the outer journey. The Intermodal Spirit. Subscribe here.

Why is this interesting?

The first ten years I lived in Tokyo—from 2000 to 2010—the city was relatively static. I mean, the whole country felt relatively static. Relative to the manic global obsession with Japan today, the country was forgotten, largely off tourism maps. Its hipster cred weirdly diminished—cool but fringe. The tiny vinyl bar JBS was running in its little nook behind Dogenzaka, but was yet to be filled by every tourist with a Raya account. You could still go to the old Tsukiji tuna auctions without issue, wander around the grounds with a camera in hand largely un-accosted. Nobody cared about you. These were, I suppose, special years in their own strange way.

The “economic miracle” dovetailing into the Bubble Years of the 80s popped in 1991. By 2000, the momentum had slowed to a crawl. Of course, none of us who had arrived to study or work in the city understood that. We were simply ensorcelled by TOKYO—the vast, all-caps, endless concrete slab spreading out before us.

Slowly, and now quickly, the face and topography of the city is changing. These last ten years feel like they’ve brought 10x more change to the city than the previous twenty. Foretold, in part, by Roppongi Hills (which went up in 2003), contemplating the rise of mega-developments from 2010 onward can send a head spinning. The pace of development was only further amplified by the run up to the 2020 Olympics. Harajuku Station, once cute, wooden, is now faceless glass and steel.

Shibuya Station, a place that saw little meaningful change for decades (and was but a nub in the early 20th century), has now gobbled up—like the hungriest of concrete eating amoeba—much of the southern side of the station. The Hikarie multi-use office/mall/performance center went up in 2012, taking out a huge swath of older, low-rise buildings. Scramble Square opened in 2019, effectively capping the old station with a new building. The Tōyoko Line was moved underground, and the previous above-ground tracks transformed into the Shibuya Stream skyscraper and Shibuya River pedestrian pathway, swallowing even more of the older, winding*rōji* alleys filled with funky bars and restaurants that encircled that side of the station. Even more development is in the works. True long-now planning. It’s awe-inspiring on many levels—the station itself has rarely hit a blip of service disruption, despite, effectively, rebuilding itself in realtime. A full ship of Theseus before-and-after.

North of the station you’ll find even more transformation—all of the once grungy Miyashita Park has been rebuilt in the style of a corporate polished modernist mall. It’s anodyne and mind-numbing and I’ll never go into any of those shops, but its presence is also oddly stimulating—the city refuses to sit still, no matter how dumb some of the stuff it builds may be.

The rest of Tokyo, too, is being pushed and pulled. Thanks to deregulation, “tower Mansions” are popping up in unexpected places—on the edge of Kagurazaka’s old low-rise *hanamachi* Geisha district, for example, much to the chagrin of the neighborhood groups. As outlined in the excellent Emergent Tokyo book, these neighborhood shop-owner collectives are organizing with more fervor than before to protect the energy and community of sometimes centuries-old neighborhoods. This isn’t NIMBYism, explicitly—it’s more like, Hey Build The Fifty-Story Tower A Couple Hundred Meters Down Adjacent To The Major Avenue Not In The Middle Of a Thriving and Vibrant Local Community ism.

I’ve been eating and drinking in Kagurazaka for decades. I love it, but to think about what it used to be—even just ten years ago—can break a heart. Something is being gained, for sure (housing units, density, access), but something else is lost in this wild maelstrom of development happening across the city.

A single-story sento public bath I used to visit in Ebisu has been replaced by a thrumming tower of humans, all largely strangers to one another. The tower houses hundreds of people and families, but the sento brought together hundreds of people. It’s fun to think about the tradeoffs of these transformations. There are rarely “correct” answers.

In my twenty-plus years of living in Japan, Tokyo feels amidst yet again another incredible phase change. If the Great Quake of 1923, the Allied firebombings of 1942-1945, the 1964 Olympics, and the Bubble Boom of the 1980s typify moments of dramatic phase change for the city, then right now—whatever this weird period might be defined as (the Cheap Flights Global InstaTok-Fueled Free-Money Selfie-Led Tourism Bump Pandemic Years?)—feels like yet another. Boomers are aging out. The Showa-born crowd of kissaten and jazz cafe and old bar owners and small-lot homeowners are dying. Batons are being passed. Thanks to aggressive inheritance tax laws coupled with incredible land-value jumps, it’s often impossible for heirs to hold onto their plots. So corporations buy them, piecemeal, until they have enough to build another tower.

Despite the questionable taste of mega-developers like Mori, Tokyo “works.” That is, it functions well and provides a durable foundation for any number of lives to be lived atop its streets. To properly walk Tokyo, giving the city your full attention and eyeballs—to bear witness to this “functioning” when so many cities today can’t seem to get out of their own way—is a gift of the highest order. To walk a city is to *feel* its change. I remember what once was on some corner, and see what is today. Not only do I remember the old shop but I remember who *I* was then. That distance bridged feels important to notice.

I’m once again walking Tokyo this week. I look forward to doing so once again, twenty-two years hence, following the same routes, seeing once again what is and remembering what was. (CM)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Craig (CM)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.