Ben Dietz | December 22, 2022

The Skate Gaze Edition

On skateboarding, seeing, and space

Recommended Products

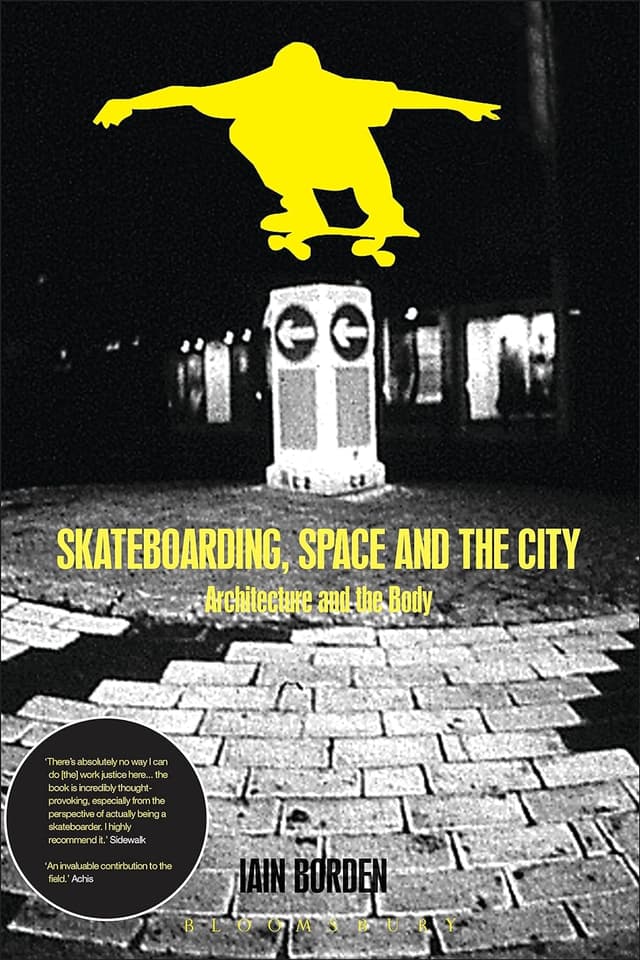

A book arguing that skateboarders draw our attention to the city as the site of perpetual change.

Re-running an all-time fave today. - Noah (NRB)

Ben Dietz (BWDD) is a longtime friend of WITI and the person behind the excellent newsletter [SIC] Weekly. He got his first skateboard as a Christmas gift in 1985 and has never seen things the same way since.

Ben here. To say I’m a skateboarder at this point in my life is to beggar belief, given that I’ve been out on a board maybe three times in the last year. But by the same token, the older I get the more clear it is to me that once you’re a skater, you can’t ever not be one. This is down to what I call (tongue firmly in cheek) “the Skate Gaze”.

The idea, essentially, is that anyone who has become a skateboarder from roughly 1985 onward (and arguably even earlier—since the introduction of urethane wheels in 1970 or so) actually sees the world in a different way from everyone else, in terms of its spatial and creative boundaries. And that skaters, unbound by a more traditional POV, are increasingly behind ideas that shape our world, literally. As the director and skateboard company owner Spike Jonze wrote to me for this piece:

I think skaters look at everything with yet to be defined possibilities. Nothing that is skated in the streets was ever creating for skating, a bench and rail, a bank, a wall...but a skater saw it and saw something else was possible there. As a skater you move through the city looking at things differently, thinking about other possibilities. And as you move into other things you want to do, that perspective just stays with you. Nothing is what they say it is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be whatever you see is possible.

Why is this interesting?

This “skate gaze” worldview is a post-postmodern phenomenon, and as such it’s only now being recognized. But considering that skateboarding is one of the most popular sports in the world (between #3 and #10 depending on who you ask), and people of all ages are staying on board longer, it’s clear that the skate gaze has implications far beyond skateparks and skate companies. As skaters age and proliferate, we can see that what Spike described as “looking at things differently” extends to every aspect of global culture. Take Alexis Sablone, a 32-year-old Olympic skater for Team USA, but also an MIT-trained architect who’s used her pedigree to design a public plaza in Malmo, Sweden that doubles as a shared skate/pedestrian space. Or Steve Rodriguez, don of New York City skateboarding and since 1996 the owner of 5Boro—a skateboard “hard goods” company, who also keeps himself busy running creative services for major advertising firms, when he’s not designing and managing the execution of New York public skateparks, in conjunction with city commissioners. They are emblematic of generations of skaters who’ve grown up seeing—through skateboarding—a world they could affect and shape by their personal actions, and they’ve seized the opportunity to shape both the physical world and culture.

When Mark Gonzales and Natas Kaupas—both now fine artists—invented “street skating” as teens in the early-mid 1980s by turning driveway embankments into launch ramps, they made the sport available to anyone with a patch of asphalt close at hand. What they couldn’t have anticipated was the incipient need 35 years later for people around the world to navigate from place to place differently. With over 50% of the world now living in urban environments, it’s become necessary for us all to travel – and allow others to travel – through public space in new ways. Echoing the explosion of bicycle travel as a statement, more and more city-zens globally are commuting by skateboard (to say nothing of those awful one-wheel contraptions, electric longboards, and the like). And there are a lot of driveways and embankments along the way.

WITI Classifieds:

We are experimenting with running some weekly classifieds in WITI. If you’re interested in running an ad, you can purchase one through this form. If you buy this week, we’ll throw an extra week in for free on any ad. If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to drop a line.

Exhibit B. Books: true crime told and sold Shop the 12 Days Of ExMas sale now

Why is your family interesting? With Storyworth, record their stories one weekly email at a time, and gift them a beautiful printed book. Get $10 off Storyworth.

Beyond this, there’s a new appreciation for the skate worldview, driven by the proliferation of skate videos on platforms from Youtube and Instagram to Tiktok. In the words of Kevin Imamura, a lifelong skater and one of the proponents of NikeSB’s push into skateboarding, “In urban areas across the globe, the amount of interaction with non-skaters feels like it is at an all-time high: average pedestrians, homeless people, security guards, etc … you see people stopping and watching what skaters are doing. They will stop and clap. The cops will allow [skaters] to finish and get the clip before they kick them out.”

Why is this, Kevin asks? Perhaps it’s because of the dual acknowledgment by skaters and by the powers that be, that neither is going away, and both have something to learn from the other. Skaters not only see physical space differently, they cause non-skaters to do so, too. There are examples of this developing around the world—as presaged by Iain Borden’s 2001 book Skateboarding, Space and the City, of which the Independent wrote: “Borden argues that [skateboarders] draw our attention to the city as the site of perpetual change.” And there are increasingly examples of civic leaders using this fact to bring vitality to their communities. Case in point, pro skater Leo Valls’ collaboration last year with his hometown, Bordeaux, to design and create a series of skate-able public sculptures, intended to bring the non-skating public closer to the action while still honoring the organic aesthetic of street skating - in which any physical feature of the landscape is potentially terrain. When skaters design, skateboarding persists.

From Leo Valls’ Play! in Bordeaux

Or perhaps it’s to do with what Chris Nieratko, former editor of seminal 90s skate-prank magazine Big Brother, observed about skateboarding as a means to relate to people, informed by his experience as a dad. As he told me, “Having a non-skateboarding, 10-year-old son on the autism spectrum has taught me a lot about myself and the skateboarding community. I think there are countless traits about skaters that can be attributed to countless skaters being undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The 100-mile stare, the deep concentration and hyperfocus on repeatedly trying to learn a trick … the anxiety, social awkwardness, lack of empathy, the flapping arms, the inherent knowledge of science far beyond their G.E.D., etc. Skaters view the world with innocent eyes for a singular use. To deviate from that is to lose the plot.”

I’m not sure. I agree with Chris that the skate gaze is singularly-focused. And I also agree that there are no shortage of people on the spectrum drawn to skateboarding—a culture that the ex-Supreme creative director and founder of skate-inspired clothing brand Noah, Brendon Babenzien, described to Monocle recently as having “invented itself.” Self-determination is a deeply attractive proposition for anyone whose reality isn’t just so. But I think the even more prevalent attraction is the way skateboarding allows its adherents to see things as more than just what they “are” but as what they could be. (BWDD)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Ben (BWDD)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.