Chris Wallace | July 7, 2023

The Peter Beard Edition

On image making, Africa, and exploitation

Recommended Products

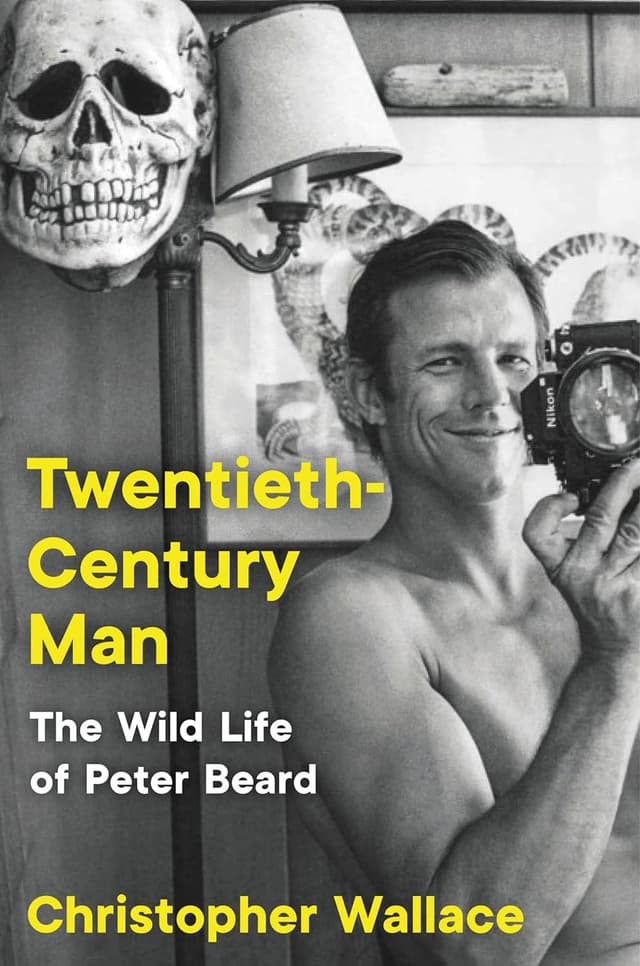

A biography on the controversial artist Peter Beard, exploring his life, work, and the creation of his powerful and lasting images.

Chris Wallace has written some great travel pieces for us in WITI. He recently published a book on the controversial artist, Peter Beard. Buy it here. What follows is a quick setup from Chris and then a Q&A between us. -Colin (CJN)

Chris here. The late photographer Peter Beard was an absolutely incredible image maker, both in his photographs of wildlife, and of supermodels in the bush, and in the buff. The image he projected of himself, too, of this kind of grand adventurer, in the tradition of the gentleman explorers gone by, was powerful, and lasting. But, in researching, reporting, and writing his biography over the last few years, in considering the ways in which he created those images, and the way he lived his life — of his behavior behind the camera and behind closed doors — I felt, at times like I was watching the whole machinery of identity and image making come apart, so disillusioned was I by by the stories I heard and had to recount. At other times, I felt like Peter might actually be a kind of portal into an understanding of all of Twentieth Century Man (and, so, the title of the book). (CW)

CJN: How did you first become aware of Peter Beard?

CW: Funny now, when we are saturated almost to numbness by what seems to be the entire history of image making, but I can’t really remember how the images might have first found their way to me. It must have been the Portraits book that James Crump put together in the 90s. I was in college at the time and Peter’s image — as in the sort of self-mythology he was projecting — lit my brain on fire. The way he was able to, in a self-portrait, even, insinuate himself into the hoary old gentleman explorer fold, into the scenarios from silent adventure films, and, I don’t know, Jungle Book, was incredible. And obviously the prints I was seeing, embellished with his own marginalia, quotes from Darwin or Thoreau, and smeared with blood and dust and things, were so potent, rich, intense, as I guess young men like things. I joke a bit in the book about how Peter was everything I am not. I was a jock. I had never left the country. And Peter sort of represented adventure and danger and drama, and it was intoxicating. I mean, we fill in the blanks, don’t we? We complete a picture, we bring it to life with all of our own hopes and affinities and aspirations. And of course, now, knowing a bit more about the danger and drama that he courted and created, both, those images, and their maker, have a much different meaning to me now.

CJN: Is Beard one of the first influencers in terms of image making and lifestyle?

CW: I sort of soft peddle the idea in the book that, among other things, obviously, Peter was the first influencer. His projection, of an identity, and a lifestyle, creating this very visually and romantically potent visual world, visual signature, was enormously influential, inspiring fashion brands and editorials. Again, he was nestling up to this other very vivid lodestone, this Out of Africa ideal that remains really alluring for people. But if we think about the lifestyle he demonstrated in his work in vignettes — from Studio 54 where he had his 40th birthday, to Montauk, where he built out a kind of New England prep gone bamboo aesthetic, to the Huck Finn Denys Finch Hatton bit in Kenya — there are whole sections of, say, Ralph Lauren or Tommy Hilfiger and the like that seem to have been drawing direct inspiration from him at the time. And if we now recognize that the construction and projection of a personal brand, of expressing selfhood, identity, politics, or whatever through our image, is a (if not the) primary mode of communication and commerce and art today, I think we have to recognize how much of that he anticipated, how much of it he articulated.

CJN: Wasn’t he exploitative on several levels?

CW: Well, yes. And let me count the ways. This is a man who built a world by leaning very heavily on his proximity to tribal culture, making props of people, and reducing culture to tropes, tokens. In his own writing, he often either flattened the experience of the guides with whom he traveled into a kind of picaresque, or else raised them up to be avatars for ideal manhood. There is a bit of fetish and othering going on, but then he was very much the main character of his mythology and all others — even Janice Dickinson when she was struggling with alcohol and Peter, she says, sort of nudged her to get hammered so that she would crawl on top of a pile of crocodiles or snuggle up to a cheetah — are supporting cast. All of which puts Peter sort of squarely in the “orientalist” tradition, the school of, say Gauguin, who was a bit of a model for Peter. Peter of course made an image, an incredible image, which he called Beyond Gauguin, which seems to imply he felt he went further than Gauguin, further from the civilized Western bourgeois society they both left back at home, to create his art. In the book, I do go in a bit on Peter’s primitiva, as he called it. This Gauguin-ish idea that beauty, or truth, about man, or life, is best found in a pre-industrialized society, preferably in the global south. And I think Peter’s main project was to tear off all of the trappings of civilized, Western society, to rewild himself, to return to a kind of First Man state of being. Like Robinson Crusoe, maybe. And, of course with his man Friday by his side.

CJN: How did his life turn out the way it did?

CW: There are a few recurring sliding doors moments in the book, in Peter’s life, at least as I insert myself into them, when we see these other lives he might have led. One of which comes during his early 20s. He’s just scraped his way through Yale and returned to his beloved East Africa to start living out this dream life he’s already had in place for some time. And there, in northern Kenya, he takes an incredible portrait of a woman, a Samburu woman. If it were someone else, another kind of photographer or person or traveler, they might’ve said, ok, yep, had our Kenyan time, did the Dennys Finch Hatton thing, now, what’s next. And that picture would’ve been the magnum opus of that chapter of his life. He might’ve gone on to become a conflict photographer, or, you know, shoot for NatGeo. But he wasn’t a photographer — as he loved to say — he really was a world builder, and that world was in Kenya. Of course with Peter being Peter, there are also mini tragedies that wipe adventures from the record. The dozens of rolls of film he shot on safaris in Namibia that fell into a fire, say. And he had all sort of great adventures that we don’t see in the work because they aren’t really a part of it — sailing around Hawaii with his cousin, Dirty Rotten Scoundrel-ing around the South of France. He joked at least once that he and Jacqueline Onassis were in the same sort of social set that went skiing together, but she certainly did hire him to be a boytoy for her sister Lee (in the guise of being a babysitter to her kids) when the sisters sailed around Greece with Jackie’s husband Onassis on his yacht. But maybe the reason those above mentioned vignettes we associate him with are so bold is because he spent a lifetime coloring them in, over and over again.