Chris Moon | February 27, 2025

The Nailing It Edition

On nails, currency, and Thomas Jefferson.

Recommended Products

A memoir by Emanuel Derman reflecting on his life in the fields of physics and financial markets.

A memoir by Emanuel Derman about his youth in Cape Town, available for pre-order in hardcover and Kindle editions.

Chris Moon (CM) is a serial hobbyist living in San Francisco. When he’s not swinging an Exeter hammer, he is saddle-stitching horsehide, aging Chartreuse, or spoofing IPs.

Chris here. Recently, while roaming through a field in Sonoma scarred by wildfire, my friend mentioned that an old barn used to stand on this particular plot. “My neighbor tells me it was likely built in the 1890s,” he told me. Reaching between patches of chaparral, he fished out an old nail. Holding it in my hand, it was a peculiar nail—flat on the sides with a stubby head and blunt tip, like a miniature railroad spike.

Why is this interesting?

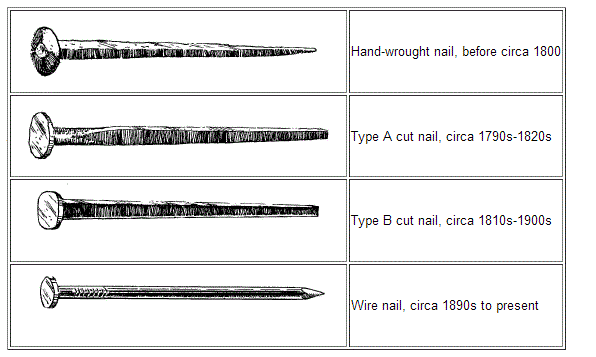

Nails weren’t always the round wire form we know today. Around the turn of the century, the design of nails changed significantly, and a pedigree spanning thousands of years was all but lost.

Nails have been produced since at least the Bronze age. (Each individual fastener was then hand forged by specialized blacksmiths, known as nailors.) The wrought and cut nails you see above were designed to take advantage of wood’s grain direction. Unlike the round shaft of a modern wire nail, the flat sides of a cut nail form a long wedge. When this wedge is oriented perpendicular to the grain, a cut nail causes the wood to form prongs, gripping with nearly twice the strength of a modern wire nail, and making it less likely to split the board.

Beyond construction, nails were often used as talismans warding off illness, nightmares, and preventing spirits from escaping their tombs. (Cont.)

Friend of WITI and contributor Emanuel Derman wrote the excellent memoir, My Life as a Quant. Now, he winds back the clock from the world of physics and financial markets with a memoir of his youth in Brief Hours and Weeks: My Life as a Capetonian. The hardcover and Kindle editions are available for pre-order at Amazon, for delivery next week.

“Brief Hours and Weeks awakens many memories of Cape Town, the city of our youth, a half century ago. The chapter on the lonely Mrs Gold is a Triumph.” — JM Coetzee, Nobel Laureate

“What a delight. It succeeds in writerly craft, narrative, evocation of people, and not least in authorial courage and candor.” — James Grant, author of ‘Bagehot: The Life and Times of the Greatest Victorian’

The tedious handmade nature of nails made them a valuable commodity, and nails were even often used as informal currency. This value is still represented in how nails are sized in the penny system (1d, 2d, 6d, etc.) This penny cost originally denoted the price per hundred. Nails were so valuable in the US colonies that laws were written to prevent colonists from burning their homes down when they moved, simply to reclaim the nails. For a time, Thomas Jefferson’s primary source of income was nail making. Writing in 1795: “I concluded at length however to begin a manufacture of nails, which needs little or no capital, and I now employ a dozen little boys from 10. to 16. years of age [to make them].” By the Industrial Revolution, the demand for a cheaper, mass produced alternative was fated, and in 1900s France, a process utilizing spooled wire was introduced. By 1913, 90 percent of nails sold in America were wire nails. Today, wire nails come in every variety and coating imaginable, from self-lubricating vinyl coated sinker nails to ring-shanked bronze boat nails.

That said, many blacksmiths and hand-tool woodworkers today still produce and collect those older wrought and cut nails, in part for their superior grip qualities. It would appear then, that the artisan trade, even after many millennia, is not quite yet dead-as-a-door-nail. (CM)