Steve Bryant | March 18, 2025

The Language Learning Edition

On scaling scaffolding, your second soul, and patience.

Steve Bryant (SB) is a longstanding WITI contributor who is slowly (very slowly) writing a curious traveler’s handbook to Mexico City. This piece was first published in his newsletter, Delightful.

Steve here. I moved to Mexico three years ago, when I was 44. The day I moved, I thought to myself: Oh, I’ll be fluent in Spanish in six months. Reader, that didn’t happen! Instead, I began the long but rewarding process of gradually becoming conversational. Fluency is a ways off, but I’m working on it every day.

Why is this interesting?

Learning a language is as much about learning about yourself as it is about learning a foreign tongue. Below, a partial list of notes of what I’ve learned along the way.

Acquisition requires repetition. And repetition. And repetition. Acquisition requires repetition.

Learn young, if you can.

Don’t not learn old, if you can’t.

Language is embodied. Have you seen those tiktoks? Of people mimicking the way actors speak? And when they mimic the way those actors speak, their faces change and almost become the actors they’re mimicking? Learning a language is like that. Language is embodied.

Duolingo only helps you embody a cartoon.

You start with the present. I am, you are, they are. For some time, the present is all you know. When you speak, you speak only about now. The past and the future, the just passed and just about to happen—you want to access them, but you can’t. You sit there in your bubble of a moment, floating in an endless present. You visualize what this state of being feels like: The light of a buoy on the ocean, flashing it’s only message. I am here, I am here, I am here.

You begin to conjugate verbs. You work with conjugation tables. These tables are logical. These tables are concise. These tables contain rules and examples. Yo hablo, tú hablas, él y ella habla. Like that. Those tables lay the language out in front of you, like all the parts of an engine, or all the parts of a toy model. And so, when you first try to speak your new language, you may find yourself perusing your conjugation tables in your head, like searching for the oil dip under the car hood, or searching for the right part amid the sprues of a plastic model sheet. Or maybe, like a maitre’d running his finger down the page, looking for the name on the reservation. What word am I looking for, what word am I looking for—ah, here it is. Right this way, sir.

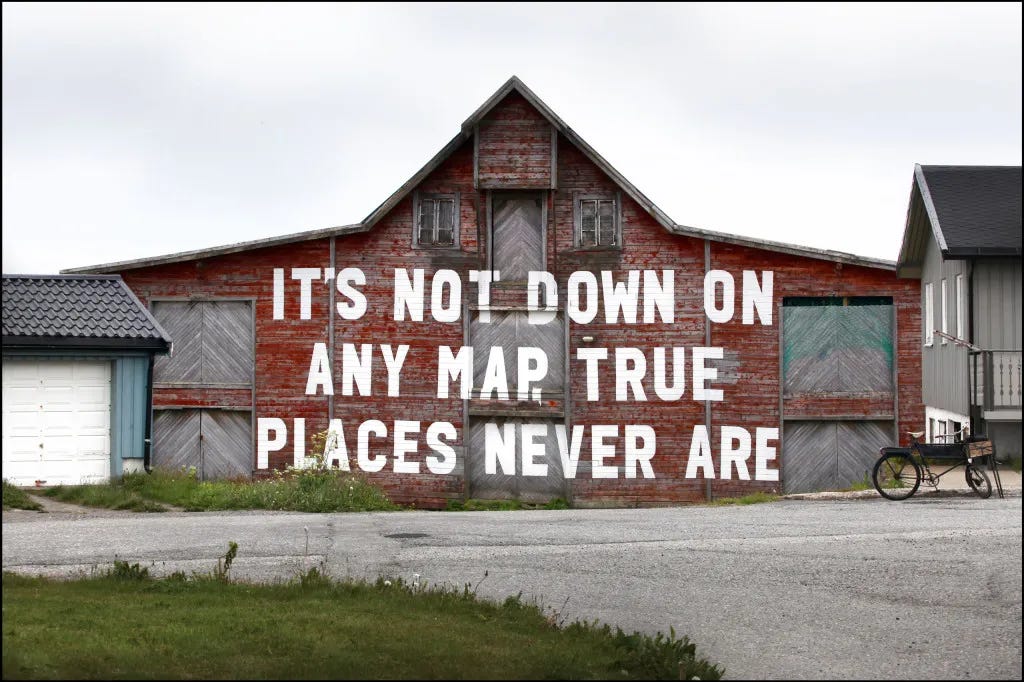

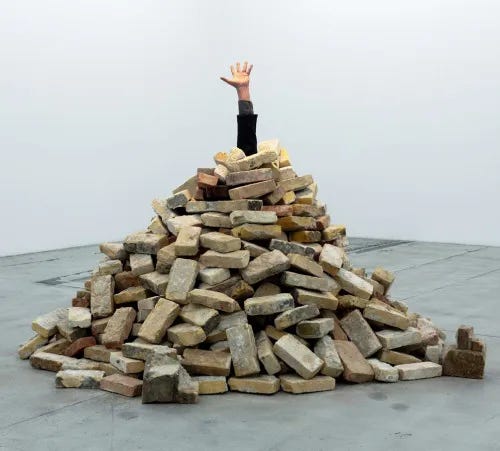

You learn the names of grammatical tenses. The present perfect, the imperfect, the conditional. You use these named tenses to demarcate zones of use. You say to yourself: I want to say I am happy about something, so that means I’m going to use the subjunctive. This takes time. You understand your new language like scaffolding understands a building.

Native speakers don’t even see the scaffolding. They don’t know, or need to know, the terms that describe the subjunctive tense, or the pluperfect, or the impersonal, or when exactly those tenses are used. They just use them. They’re inside the building. You are outside on the scaffolding, climbing from one floor to the next, speaking into the windows.

Language is emotional. Learning is an emotional reaction. You won’t be any good if you’re not having any fun.

You realize your fluency, or lack of fluency, informs how you speak. You can’t choose the best word, or sentence, or phrase if all the possible words or sentences or phrases, or at least a selection, aren’t available to you. In your new language, you are less than you were. You say the same thing over and over again. You think: I wonder if this is how shy people feel, in their native language. Or maybe this is why people get angry, or aren’t adept emotionally, in their native language. Is it because they don’t have the words? That they can’t see the words, or access them, or even know they exist. Do they know they don’t have the words? Does this make them angry, too? Is most of our anger, when trying to communicate, at ourselves?

You begin to realize: your native language, the way you’ve adopted it and molded it to your use, the way you’ve chosen favorite words, favorite quotes, favorite sayings, your sense of timing, your tone of voice, your actual voice: this is armor. You are behind your language.

You also realize: Those language choices you’ve made—remember when you heard a friend say something in high school, and you’ve been saying it ever since?—are also your way of interrogating the world. You send your sentences out like scouting parties, seeking, probing, touching, gathering intel, waiting for what comes back. In your new language, you need new scouting parties, differently equipped.

It’s said that learning a new language is like getting a second soul. What is this second soul that you’re creating? How does it feel?

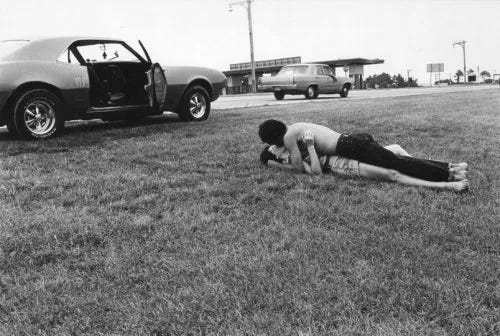

You go into it thinking the shortest phrases, the quickest exchanges, those will be the easy ones, but the short ones can be the hardest to deploy. You’ll be caught for lack of a word, or a fault in pronunciation. A tractor, backing up again and again, failing to catch its hitch.

All the world wants to practice their English, and people are quick to practice with you. It will be harder to speak your new language with people who speak English well. Miss one word, flub one pronunciation, they’ll be quick to switch to your native tongue. Trying to learn a language when surrounded by people who speak English well is like trying to get into the subway car while everyone else is trying to get out.

Seemingness is the enemy. Wanting to seem like someone who speaks another language well, rather than trying to be someone who speaks another language well, will hinder your progress.

Speaking is one thing, understanding another. The hardest thing is understanding other people. The hardest thing is letting your ear become acclimated to strange sounds, strange combinations, different tones. When learning a new language, you can’t do that thing you in your native language: wait to speak. Instead, you must wait to understand.

Your ear begins to get better. The melodies begin to have meaning. You begin to resolve sounds into words. Some sonic key gradually molds itself into the shape of a lock, every day.

The universal translator will prevent you from changing your own brain, but with the universal translator you will also have experiences you never would have had, which will change your brain.

It’s not: you can’t have a conversation in the language and then presto, you can have a conversation in the language. Rather, it’s: presto, you can have a conversation in the language, but only with one person at a time. Or: you can have a conversation in the language, but not really in crowded rooms. Or: you can have a conversation in the language, but not with people who have different accents. Or: you can have a conversation in the language, but not with the very young, or the very old, or the very sober. A new language is a map, and you don’t have travel papers for every country yet.

Talk to strangers. Make everybody not a stranger. Come home every evening with a story about somebody who is no longer a stranger.

Play games in your new language. Board games, card games, dice games. The confined rhetorical space teaches you new verbs and provides a safe space for experimentation.

Don’t be the person who only knows a few words but throws them into the conversation at every available moment. That person is trying to seem.

Practice accent from the jump. Find a person whose accent you enjoy. Emulate that.

Be vigilant if your partner speaks your native language. Don’t let yourself be lazy.

Seek out embarrassment. Embarrassment is the best teacher.

(SB)