Sam Valenti | February 4, 2025

The Bootleg Edition

On beating (then eventually becoming) the real thing.

Recommended Products

An excellent book providing scholarship on bootlegging as a creative practice, released in 2024.

Sam Valenti (SV) is an old friend of WITI. He’s the founder of Ghostly International and runs the essential music Substack Herb Sundays.

Sam here. Even though GQ famously decreed last year that the merch era was over, one could argue that merch—and bootleg merch—will never die. In fact, it’s as alive as ever.

Bootlegging is no longer the scourge of all brands and bands, unless you're say, a handbag maker (even that classic feud has since been mined for media attention). Today, it is standard practice in creative spaces. There’s even scholarship now, including 2024’s excellent UNLICENSED: Bootlegging as Creative Practice. The grey market cycle continues—contemporary bootleg pioneers Boot Boyz just announced their own screen printing company. As they say, the wheel turns…

Why is this interesting?

In the '10s, luxury brands started to see the appeal of unauthorized goods. Between 2015 and 2022, under the creative direction of Alessandro Michele, Gucci sanctioned official items by artists known for bootlegging, like Guccighost, and even bootlegged themselves. Culture jamming from the inside, not unlike wacky social media voices, had arrived.

Today, the crowded collaboration field is a form of legalized bootlegging, and we are only beginning to make sense of it with some distance. Kaws, for instance, started as a graffiti artist known for mixing his work into street posters, but now has the keys to franchises like Sesame Street via Uniqlo. They allow him to “x” out the eyes of their beloved characters – IP that would have been sacrosanct in any previous era.

Modern merch has formed a virtuous cycle between vintage, bootlegging, and reissues. Vintage becomes the proving ground for the value of merch (the $1000 Nirvana tee is a canonical baseline). The bootlegs that follow show the demand for more products as a form of street-level R&D that then can encourage brands to recommit to making new stuff. Even furniture brands like Ikea are in on the act of pulling from one’s own archive.

Just as late-night TV juices its programming to output meme-able clips for social pulls the day after, if your brand can’t be bootlegged, it's possible your signal strength isn't high enough. As the late designer Virgil Abloh famously said, “You haven’t made it until you’re getting bootlegged.” WITI’s Noah Brier played with this concept with his BRXND CollXbs project, using AI to see which brands “made it through” the prompt stage into something recognizable. He said agencies often preferred these outputs to sanctioned collabs.

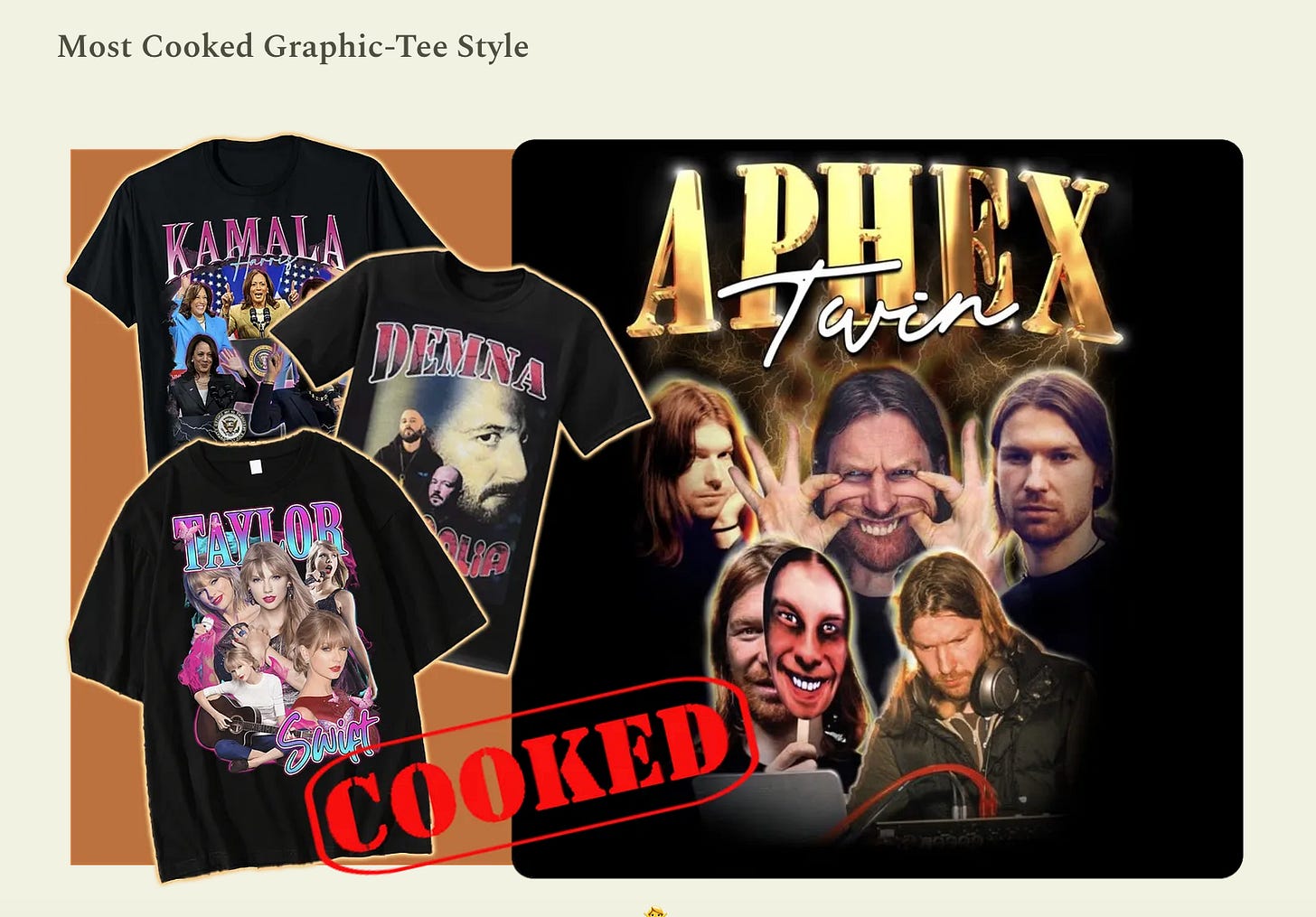

Bootlegging as a purely aesthetic form has been re-appropriated so many times that it’s perpetually at risk of losing its subversive oomph. After merch from failed financial institutions like Bear Stearns became vintage gold, this was inverted with “legit” Enron gear – sold through the brand’s now legal IP holder. If you turn the dial past its limit, the art for the Aphex Twin rarities compilation from December portrays a faux bootleg look, a double inversion. Blackbird Spyplane might have already denounced this faux-faux look (below), but that doesn't mean it won’t keep moving ahead.

New York’s Night Gallery makes artful homage tees as part of its repertoire, and I asked its designer Josh Zoerner what he believes artists feel about his work: “From my experience, bands really enjoy and engage with people who interpret their art or world in a different but true or authentic way. In a culture where everything can be and often is remixed, the bootleg can function as an extension of the artist's aura.”

The music industry has traditionally (and predictably) looked down on bootlegs. However, with increased pressure to find a track that strikes as a viral moment, licensed or not, major labels are starting to look the other way if it means finding a ‘legitimate’ success. An unsanctioned remix of Madonna’s “Frozen” from 2021 started as a TikTok hit, and was then signed and released to become a top 5 Madonna streamer for a period.

Some bands have shown the way of course, like the Grateful Dead, who were amongst the most ardent supporters of the bootleg merch and music concept, creating a fan ecosystem before the term UGC existed. Bands like Pearl Jam have followed suit, creating a healthy aftermarket for legal show recordings.

Brand-builder and cultural reporter Ana Anjelic (whose excellent The Society Of The Spectacle piece firms up a lot of key ideas here) offered me this note about why this may be happening:

“To me, bootlegging is probably the most creative form of production in retail today. In the context when styles are copied at the speed of the social media algorithm (Shein, Zara), and when the time between a new look and its mass market copies is very compressed, bootlegging reaches the level of craft. It takes talent, and time, and quality materials to bootleg something, as well as a personal imprint. Human copy will always beat an algorithmic one.”

As someone who watches this stuff, I can agree bootlegs often sometimes feel more “real” than the mass market versions many brands (and bands) spit out these days. The best ones feel like an authentic act of devotion. One of my favorite hats in my closet isn’t my original The Gates cap (purchased on-site in Central Park), my Sony Pictures Classics hat (a 2017 Depop find), or my Arthur Russell piece (an official bootleg/collaboration between my company Ghostly, Arthur Russell’s estate, and Audika Records). It's a cap that says “Mickey Drexler”, an edition of only nine made by WITI comrade Reilly Brennan.

It’s not the scarcity or sentimental provenance that makes this cap great, but a third thing: a bottomless wealth of romantic intent. Brennan makes these “privates” (a riff on “private press”) for friends as some “atomic form of fan fiction.” Bootlegs like these further split our timelines and canon. No faceless companies produce them: Instead, eccentrics who want to create something that only exists in their brain—or exists already, but at a price point they can’t reach—conjure these items out of practically thin air. These people will always exist, and so will the sacred bootleg. (SV)