Russell Davies | October 6, 2022

The Acrostic Edition

On credit, hidden messages, and the power of revenge

Recommended Products

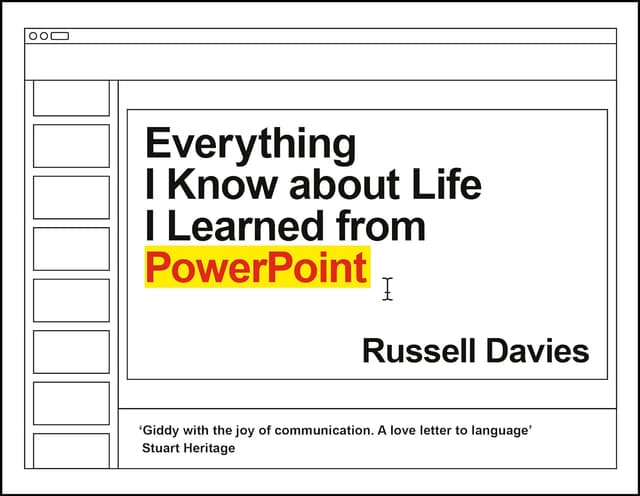

Russell Davies shares insights linking life lessons with PowerPoint, offering an intriguing perspective on how this ubiquitous software can reflect and inform life strategies.

Russell Davies (RD) is someone I met on the internet a long time ago. If you were a marketing strategist in the mid-2000s, you probably read and were inspired by Russell’s blog (which he’s been pretty active on lately). He was kind enough to give many of us time and show us the joy of putting ideas into the world. He’s got a new book on PowerPoint that’s called Everything I Know About Life I Learned From PowerPoint. - Noah (NRB)

Russell here. Way back in the 20th century, a London copywriter called Richard Cook wrote an ad that won an award, but the award didn't include his name in the credits. He thought that was pretty bad form from his bosses. Young creative careers depend on this kind of acknowledgement, so the next time he wrote a potentially award-winning headline he hid the words Richard Cook Wrote This as an acrostic in the copy. In case a random act of typesetting upset his plan he made sure the whole agency was in on it—sometimes a minor moment of pettiness takes a village. Sure enough, the ad did indeed win an award, appearing in the prestigious D&AD annual (with his name in the credits).

There is a long, honorable tradition of protests like these; early in the Trump administration the President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities resigned en masse with an acrostic that spelled out RESIST and a science envoy buried the word IMPEACH in his resignation letter. Highlighting content-producer abuse in a very suitable way, in 2015 Jack Urwin concealed PAY WRITERS in a piece he wrote (for free) for the Huffington Post. In 2009 then Governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger sent a memo to a state assemblyman in which the first letters of lines 3-9 spell "FUCK YOU." Said the Governor: “It was a coincidence.”

In 1992, James May, then editor of Autocar, was fired for using the large red initial at the beginning of each car review to spell out "So you think it's really good, yeah? You should try making the bloody thing up; it's a real pain in the arse." Noted poet Rolfe Humphries wrote a piece for Poetry magazine in 1939 that spelled out "Nicholas Murray Butler is a horses ass." across the first letters of each line. Textbook literary pettiness.

Why is this interesting?

Every one of us has probably written an acrostic at some point—but likely as a slightly lame writing exercise during a dull English class. Rewarding to read they ain’t, like most puzzles in art they’re interesting when you read about them and tedious when you have to sit through them. Except maybe acrostics will find new life in the vast tracts of landfill content we’re strewing across the internet. Surely all those underpaid writers, still cheaper than AI, are sneaking submerged snark past their equally underpaid editors and sticking it to their platform rulers.

Take a minute, if a piece you’re reading seems jarring or strangely worded, and look out for hidden meaning; maybe it’s marketing copy secretly dissing the product, or T&Cs with hidden declarations of love, or an editorial concealing it’s own opposition. I love to imagine all the timebombs out there. Neglect an oddly turned phrase and you might be missing gold. Give it a second glance, someone might be trying to tell you something. (RD)

—

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Russell (RD)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.