Matt Locke | February 10, 2022

The Warhol Album Cover Edition

On albums, constraints, and collaboration

Recommended Products

A 1957 Prestige album by the blind, avant-garde street musician Moondog. The cover, entirely handed over to Warhol's mother's flowing, looping script, features text literally telling the story of Moondog. Finished by Reid Miles with alternating vivid greens and blues.

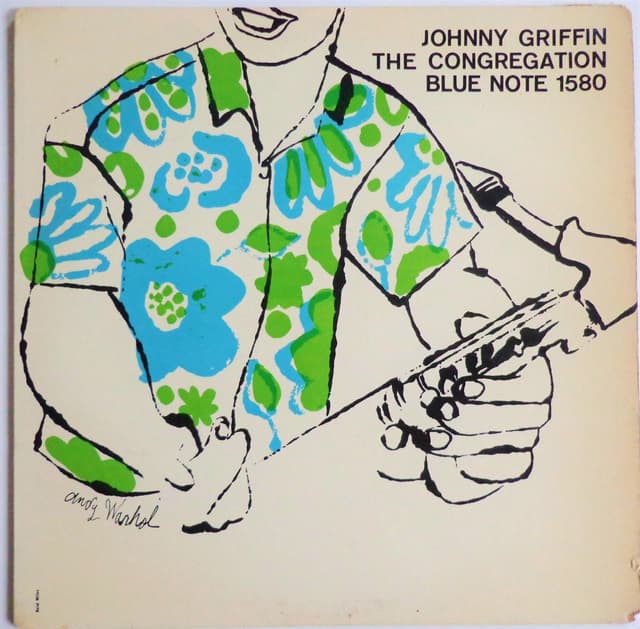

The cover of Johnny Griffin's 'The Congregation' features a vivid blue and green flower pattern, with a dip-pen ink line, tracing Griffin’s relaxed pose with his saxophone. It's an early example of Warhol's style, done in collaboration with Reid Miles.

Matt Locke (ML) is a WITI reader and the Director of Storythings, a content studio in the UK. He previously wrote the UK Baseball Edition and the TV Schedule Edition.

Matt here. Andy Warhol produced two of the most famous and notorious record covers of all time: the ‘banana’ cover for Velvet Underground and Nico, and the Rolling Stones “zipper” cover for Sticky Fingers.

But these weren’t one-offs—Warhol was a prolific record cover designer, creating over 100 covers during his career. He started working as a freelance illustrator in NYC in the late 40s and was commissioned to make his first record cover design for Columbia in 1949. The album was a recording of a concert at MOMA from Carlos Chavez and a mixed American/Mexican orchestra. His illustration, featuring the spidery dip-pen ink style he’d used for fashion magazines and adverts, takes up barely a third of the cover, crowded in by the serif text. But it was the start of one of the most interesting threads through Warhol’s career and gives an early sign of some of the concepts that were crucial to his later work.

Why is this interesting?

Warhol’s early record covers demonstrate how he learned to work with two concepts that would end up defining his career as an artist: constraints and collaboration. The constraints set by clients, collaborators, and mass production were recurring themes, and you can see how he learns to play within (and later stretch) these constraints in his record covers.

My favorite Warhol record covers come from a collaboration with one of the masters of record cover design: Reid Miles. Warhol had already worked on covers for jazz artists at RCA Victor and Columbia, and Miles hired him to work on six covers in total—three for Prestige, and three for Blue Note. For many of these Warhol worked from photos of the musicians taken by Francis Wolff, the photographer who Miles commissioned for many of his most iconic Blue Note covers. Warhol’s adaptions of Wolff’s photos, reducing them to black lines and pops of flat color, are early experiments of the style he would use in his later silk-screen paintings of Elvis, Jackie Kennedy, and Marilyn Monroe.

I vividly remember seeing the cover of Johnny Griffin’s The Conversation in a record shop in Glasgow in the 90s. I bought it on the spot, not even caring about the music because I had to have the cover. The vivid blue and green flower pattern pops out at you, and the dip-pen ink line, tracing Griffin’s relaxed pose with his saxophone, has a fluid grace that echoes the music inside. You can almost hear the chinking glasses and appreciative murmur of the jazz-club crowd just looking at it.

But there was another collaborator that formed an unlikely triad with Warhol and Reid Miles: Warhol’s mother Julia Warhola. Julia, who moved to New York in 1951 to live with and look after Andy, was a keen artist herself, drawing cats, singing Russian Folk songs, and making collage constructions of flowers with tin cans and grocery packaging (which he later claimed as an inspiration for his soup can paintings). When he returned from traveling as a young man, Andy would ask Julia to write captions in his drawing sketchbooks, and when he started working as an illustrator he would often ask her to do the same on his commercial work.

For the cover of The Story of Moondog, a 1957 Prestige album by the blind, avant-garde street musician Moondog (featured in WITI’s Moondog Edition), Andy gave the entire cover over to his mother’s flowing, looping script, with a text literally telling the story of Moondog. Warhol gave the finished black drawing to Reid Miles, who then colored the sentences into alternating vivid greens and blues. The cover won a Certificate of Merit from the Art Director’s Club of New York, crediting “Andy Warhol’s Mother” as the creator.

So what did Warhol actually contribute to this cover? He didn’t write the text or layout the final design, but he was pivotal in making the collaboration happen. He’d already started to move from the modernist ideal of the artist as sole creator, to something new: the artist as a director or facilitator, someone who made things happen around him, rather than making the work himself.

You can draw a line from this collaboration with his mother, through the ever-changing cast of collaborators at The Factory, his work with Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver, managing The Velvet Underground, right up to his later collaborations with Jean Michel Basquiat. The Moondog record cover marks, perhaps, the moment Andy Warhol moved from being an artist to being a brand. (ML)

Warhol Album Cover of the Day

In 1955, Warhol illustrated this cover for a Count Basie LP on RCA Victor. It’s thought to be Warhol’s first celebrity portrait, based on a photograph of Basie given to him by the record company. It’s the only jazz album cover he did that depicted the artist’s face, and closely resembles his later screenprint celebrity portraits. It’s a precursor to the album covers he made in the 1970s and 80s, when Warhol used his silk-screened celebrities portraits on record covers for many artists, including Diana Ross, Aretha Franklin, and—surprisingly—Paul Anka. (ML)

Quick Links:

The brilliantly titled Andy Earhole is a collection of blogs by Warhol record collector Guy Minnebach in Belgium. It was an invaluable resource for this WITI, and well worth diving into if you want to find out more. (ML)

In 2015 the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills hosted a comprehensive exhibition of Warhol’s record covers. The gallery guide has a great essay you can read online as a PDF. (ML)

The Velvet Underground & Nico LP was published in a dizzying variety of editions. Uber-collector Mark Satloff has over 800 copies of the same album in different versions. (ML)

--

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

The data-driven enterprise of 2025. Is data embedded in every decision, interaction, and process at your organization? Too often, the answer is no. By 2025, smart workflows and seamless interactions among humans and machines could be as standard as corporate balance sheets, and most employees will rely on data to optimize their work. Need a guide? A comprehensive new look at the data-driven enterprise of 2025 can help.

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Matt (ML)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).